Galleries One & Two

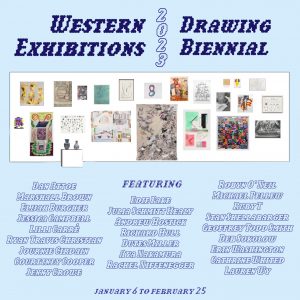

Western Exhibitions is thrilled to present the second Western Exhibitions Drawing Biennial, a celebration of the medium of drawing in many expanded mutations. Contributions by gallery and affiliated artists confirm the gallery’s commitment to drawing and works on paper and the varied approaches on view — from schematic to free-form, in-your-face to speculative, abstract to figurative — will capture the current state of contemporary drawing practices while placing a focus on gallery artists’ core concerns of personal narratives and cosmologies, identity and gender, sexuality, pattern and exuberance, all with a keen attention to materiality. The inaugural WXDB, in 2021, presented multiple works from each artist. This iteration is different: participating artists will present just one or two pieces – some created specifically for this show, others pulled deep from within the artist’s archive – to concentrate the viewer’s focus and reward careful looking. By continuing the idea of a Drawing Biennial, Western Exhibitions stakes a claim that drawings are to be lauded as much as painting, sculpture, and any other medium, as the gallery reveres the handmade, the tactility, the immediacy of drawing. From the essay by Shannon R. Stratton, commissioned by the gallery for the 2021 show: “Drawing is space to make visible the contents that make us, to make material, and then examine, those qualities that are much more complex than the linguistic code applied to them.”

Critic Erin Toale reviewed the inaugural Western Exhibitions Drawing Biennial in New City, expertly capturing the gallery’s devotion to the practice of drawing:

Drawing. A medium that is foundational, yet often relegated to the planning stages: just a sketch, rarely the main event or finished product, something unearthed after the death of an artist or architect to demonstrate their rendering accuracy. This biennial, however, is not drawing as a first draft, a prompt, or the beginning of something. This is the gallery declaring its commitment to drawing in a public ceremony. This is the evolving mission and history of the space as told through multiple panoramic storyboards, each artist with a vignette contributing to the overall narrative.

The Western Exhibitions Drawing Biennial will open the 2023 art season with a reception, free and open to the public, at our Chicago location on Friday, January 6, from 5 to 8 pm and will run through February 25. Gallery hours are Tuesday to Saturday, 11am-6pm and by appointment.

Read a review of the show by Lori Waxman in HYPERALLERGIC here.

Access an enhanced PDF to see available work and details here.

Participating artist bios:

Dan Attoe’s paintings depict natural wonders populated by tiny figures spouting even tinier diaristic missives culled from the artist’s stream of consciousness. Attoe makes a small drawing every day that he keeps for himself—slightly larger drawings and paintings expand upon this practice. His drawings share the same concerns but inverted—the phrases and disconnected images are larger and often cartoonish, creating small-scaled narrative vignettes.

Marshall Brown is an architect, urbanist, and futurist whose work creates new connections, associations, and meanings among disconnected architectural urban remnants. Moving between various scales of architecture and diverse conceptual frameworks, Brown’s collages embody new relationships between the one and the many as he expands the boundaries of reality.

Elijah Burgher creates structured, hieratic compositions in his coloured pencil drawings, matching figuration to abstraction in a provocative tension. A simplified approach to pencil technique and colour along with an attention to paper as a light source allows for heightened luminosity.

Jessica Campbell’s satirical drawings, comics, and textiles expose the everyday experiences that reveal the sexism women have faced throughout history, and especially presently. She infuses a vulnerably humorous tone into her work, but underlying this humour is often a darker subject matter that directly or indirectly references themes of class oppression, sexual violence, gender discrimination, trauma, or other personal narratives.

Lilli Carré’s interdisciplinary creative practice employs a wide range of media including drawing, animation, comics, printmaking, and ceramic sculpture. Representations of the malleable animated female body throughout history are a constant source of fascination for Carré.

Ryan Travis Christian carefully and densely layers graphite to reveal high-contrast graphics and dizzying patterns in his small-scale drawings. Impacted by Chicago-style figuration, Christian focuses on the paradoxical relationship between childish cartoons and ominous messages, musing on the technological and material obsolescence of his inspiration.

Journie Cirdain thinks of the drawing surface as a locus for thoughts, puns, personal narrative, scraps of information, remembered art history, daydreams, desires and other tangled remnants of everyday life to become magically visual. Often, these drawings are directed by a word, object, or the artist’s actual body, which is placed, like a stone, into the center of the surface. A wide range of scratches, scribbles, smears, and detailed drawing techniques reveal the system of connections which ensue.

Courttney Cooper is a vernacular artist from Cincinnati, Ohio who is known for drawing large-scale cityscapes of his hometown that respond to changes in the city’s architecture and environment. Cooper’s practice is a perpetual celebration of Oktoberfest Zinzinnati, USA, a commemorative and nostalgic place that exists parallel to or as a transparent layer upon Cincinnati, Ohio.

Jenny Crowe uses fragments of truth and information to create visually complex and powerful images. Somewhere in between poetry and painting, Crowe’s words are layered and overlap enough to visually flatten themselves. She works methodically from left to right and top to bottom filling the void of empty space until the viewer is trapped somewhere between the impulse to read and a purely visual experience.

Edie Fake’s precise paintings and drawings start as self-portraits. From there, they make a break for it as Fake references elements of the trans and non-binary body through pattern, colour, and architectural metaphor. His intimately scaled gouache and ink paintings on panel are structured around the physical aspects of transition and adaption as well as mental and sexual health.

Julia Schmitt Healy’s early work embodies the Chicago Imagist scene in the early 1970s. Her drawings on handkerchiefs and sewn flour bags present connections to real people, places and things through a lens of symbolic surrealism. Her work focuses on themes ranging from ecological disaster, human relationships, symbols, feminism, consumerism, and the natural world.

Andrew Hostick is self-taught, taking as his subject the advertisements and reproductions found in various art magazines including Art in America and Artforum. In each drawing Hostick inscribes and scores the mat board with heavy-handed marks, slowly building up a velvety sheen of coloured pencil. The resulting works constitute a beautiful collapse of both primitive and contemporary sensibilities, commenting directly on a sort of voyeuristic access to an Art World largely inaccessible to the artist as an outsider practitioner.

Richard Hull’s crayon drawings curate conversations between colour and form. Hull’s portraits and hairdos express distinct visual personalities rather than legible representations of specific individuals. He calls his over-capacitated, robust, mysterious heads “stolen portraits.”

Dutes Miller examines the spaces where the artist’s inner life, queer subcultures, and mass media intersect in his collages and artist books. Appropriating images from pornographic websites, magazines, and his own imaginings, Miller investigates alternative standards of beauty, visualizations of lust and desire found on the internet, and power dynamics in sexual relationships. His work critically engages with the mythologies surrounding human sexuality, especially the exploration of the male body as it manifests itself in gay desire—in its evident state of arousal, its protuberances, and its emissions.

Aya Nakamura’s work is influenced by a philosophy of mind, derived from interacting with plants and following post-humanist research in biology and anthropology, that does not exclusively locate consciousness in the human. Variegated lines move across, alongside, and info fields of colour in Nakamura’s coloured pencil drawings on handmade paper of different sizes and shapes. Some have visual links to existing symbols and objects which provide starting points and themes within amorphous compositions, simultaneously building and dissolving the more time is spent exploring the compositions.

Rachel Niffenegger’s work focuses on the ephemeral state of the feminine figure in contemporary society, addressing notions of the body, sculpture, clothing, and painting. She allies to both physical and psychological violence in her stained fabrics, horror-themed watercolour paintings, and mixed media sculptures; all preoccupied with fecundity and the macabre, Niffenegger’s drawings are at once psychedelic and mysterious.

Robyn O’Neil’s precisely drawn graphite landscapes investigate evolution, apocalypse, natural disaster, and extinction with imagined imagery that is surreal, and separate from the flow of time. Ominous clouds and landmasses, monks, ears, mysterious female figures, faceless busts, and other enigmatic characters float over craggy and rolling landscapes illuminated by strange—almost heraldic—light, cast through mystical clouds, calling to mind Pre-Renaissance painting.

Michael Pellew is a Brooklyn-based artist who is known for his humorous rumination on pop culture and celebrity mash-ups. His inspiration comes from speed metal, Taylor Swift, Chicago Deep House and reality TV stars. Michael’s seemingly simple and succinct drawings use playful line quality and imaginative cultural observations to develop an alternate universe where pop culture is thrown into a blender, giving the viewer random moments that are exuberant, painfully honest, witty and at times, grim.

Stan Shellabarger‘s drawings in the Western Exhibitions Drawing Biennial are made by walking on paper laid over an aggressive surface while wearing shoes with graphite-impregnated soles, a tangible extension of his endurance-performance actions, often enacted from sunrise to sundown on solstices and equinoxes. Shellabarger’s performances, works on paper, prints and artist books employ alternative drawing methods to address how the body relates to the Earth. He takes everyday activities—walking, writing, breathing—to extreme measures in endurance-based performance work that amplify the traces humans leave on the Earth. Repetition of an activity leads to a massive accumulations of marks, thus creating drawings that record discrete units of time and space. This repetition is necessary so that otherwise extremely subtle marks emerge as visible artistic interventions.

Geoffrey Todd Smith creates complex, rule-based abstractions that place him firmly within the orbit of modern American art, but with a wandering eye to the future. His vision is guided by self-imposed limitations that instill order to an otherwise meandering dream-like process. The result is a stylish eruption of concentrated color and form, enveloped in a hand-drawn web of doodled spikes and ruffles and embedded with a rhythmic plague of polka-dotted interference. The playfully constructed titles for each work provide an additional climate of atmosphere and mood without completely revealing a narrative.

Deb Sokolow’s semi-abstract diagrammatic drawings reference aerial views and floor plans. Their titles propose humor and criticality with regard to the built environment, institutions and the foibles of world leaders. Sokolow’s schematics often appear to be reproduced with a printmaking process. Instead, they are hand-rendered with colored pencils and crayons and function as a conceptual compliment to their speculative titles in that they contain a level of uncertainty with regard to the fabrication of content.

Ruby T is a drawer who is fuelled by anger, desire, and magic. Her practice is equal parts performative and devotional, and her drawings and marbled silk paintings are translations of political and sexual desire. For the past few years, she has been preoccupied with drawing moving water —particularly the impossible act of representing it— landing recently on the process of marbling, which essentially is a print of the surface of water.

Erin Washington’s paintings and drawings combine imagery, text, and fugitive materials to evoke a long history of human inquiry into the form and meaning of the universe we live in. In these works, perception, and permanence are called into question, while elements of theoretical physics mingle with images of tangible objects from antiquity. These multilayered works consist of a medley of ambiguous scientific diagrams, art historical references, Post-it notes, studio debris, mythological figures, and self-deprecating jokes.

Cathrine Whited writes lists as the first step in her art-making process. She then draws each item on the list, rendered in her unique way of framing and labeling the item before cataloging the list’s drawings together as a unit. For instance, with a list entitled, “What’s in my fridge?” every possible item that is in the fridge is labeled. She starts a drawing with a ruler, making guidelines in pencil, to then render the imagery and text. Colored pencil is then applied for the right amount of color before moving to the next item on the list. Her renderings are a vehicle for viewers to isolate, experience, and analyze our collective everyday interaction with the objects and culture that surrounds us.

Lauren Wy practice is rooted in the anarchy and immediacy that can be located in expressive mark making, utilizing acid color and expressive figuration to investigate obsession and possession, ritual submission and dominance, alienation and presence. The materials and formal elements of her images work as a method of reduction into the base elements of our collective psychological condition, asking questions of control and self authorship. Ultimately it is always brought back to desire and the power structures that code the

formation of selves as evident in the constant slippages between figure and abstraction